Minting policy¶

A minting policy is the set of rules that govern the minting and burning of assets scoped under that policy. The point of a minting policy is to specify the conditions under which tokens are minted (or burned). For example, the rules might specify who has control over the asset supply through minting and burning.

Minting policies are defined by the users who want to create a new asset. For example, a user might wish to only allow themselves to mint any more of a certain kind of token. This would be specified in the policy.

Minting rules can be expressed:

As very basic set of rules that is made up of (ANDs and ORs of):

A specification of what signatures are needed to allow the mint (eg, a multisig specification, where no code is needed).

A specification of during what slot the script can be spent from (eg, after slot 15 and before slot 20)

With a Plutus Core script

Adherence to minting policies is checked by the node at the time a transaction is processed, by running the code or checking the relevant signatures. Transactions must adhere to all the minting policies of all assets that the transaction is attempting to mint.

Important points about minting policies and assets scoped under them¶

All assets necessarily have a minting policy. For example, the minting policy of ada is ‘new ada can never be minted’.

A token is associated with (eg, scoped under) exactly one minting policy.

A single policy specifies both minting and burning conditions of tokens scoped under it. Adherence to it is checked both at the time of minting as well as burning.

An asset cannot ever change its associated minting policy. This association is permanent. In other words, existing tokens cannot be associated with a new policy. Users can, however, buy back and burn all existing tokens and mint new ones, with a new minting policy. Note that this is a feature, not a bug.

If an existing asset on the ledger is scoped under a particular policy, it is guaranteed that it was originally minted according to that policy.

Unless tokens of a given policy are being minted in a transaction, the actual policy is irrelevant. It is just used as an identifier of the asset.

Assets associated with different minting policies are never fungible with one another. They can be traded in the same way one may use USD to buy CAD: the amount of CAD you can buy with a fixed amount of USD depends on the exchange rate of the place where you do the trade.

Association between an asset and its minting policy¶

The association between an asset and its minting policy is permanent for safety reasons: this feature protects the users and the system from illegitimately minted tokens.

If the minting policy of a token changes, it is not really the same token any more, and its value cannot be compared to that of the original token. This permanent asset-policy association scheme is integral to defining high-assurance policies. Loosening this identification opens the MA scheme to various attacks. Having a permanent association between these allows us to guarantee that every token was minted in accordance with its minting policy, and not any other policy which it might have previously been associated with.

Note that this is not as restrictive as it sounds. In a loose parallel with US monetary policy, we can say that the policy is ‘government and laws set the policy’, and this is a policy which requires looking up the current laws (which themselves could change), and only minting money in adherence to them.

Minting policy examples¶

Single-issuer policy

Time-locked mint policy

One-time mint policy

Note: There are many other types of minting policies.

Single-issuer policy

A single-issuer minting policy specifies that only the entity holding a particular set of keys is allowed to mint tokens of the particular asset group. For example, the set of keys specified in the minting policy must have signed the minting transaction.

An example of an asset group that would use a single-issuer policy would be tokens representing baseball cards. The company manufacturing legitimate collectors’ cards would publish the keys required by the minting script to mint new baseball cards. This would mean that no new baseball card tokens can be minted without the company’s signatures. This type of policy can be implemented without Plutus smart contracts.

Time-locked minting policy (token-locking)

This type of policy can be used to specify when tokens can be spent from an address. In particular,

only in or after a specified time slot

only before a specified time slot

This type of policy is usually not used by itself. Usually, it is in conjunction with the multisignature or single issuer policy, e.g. This output can be spent after slot s and only by a transaction signed by key k.

This type of policy can be implemented without Plutus smart contracts.

One-time minting policy

In a one-time mint policy, the complete set of tokens of a given asset group is minted by one specific transaction. This means that no more tokens in that particular asset group will ever be minted. This type of policy needs Plutus smart contracts to be implemented.

One-type mint policies would be useful for generating concert ticket tokens for a specific concert, for example. The venue capacity is known ahead of time, so there’ll be no need to ever allow more tickets to be minted.

Minting transactions¶

To introduce new quantities of new tokens on the ledger (minting) or to remove existing tokens (burning), each transaction features a mint field. The transactions where the mint field is not empty are known as minting transactions. The use of this field needs to be tightly controlled to ensure that the minting and burning of tokens occurs according to the token’s minting policy

Apart from the mint field, minting transactions must also carry the minting policies for the tokens they are minting, so that these tokens can be checked during validation.

The outcome of processing a minting transaction is that the ledger will contain the assets included in the mint field, which is included in the balancing of the transaction: if the field is positive, then the outputs of the transaction must contain more assets than the inputs provide; if it is negative then they must contain fewer.

It is important to highlight that a single transaction might mint tokens associated with multiple and distinct minting policies. For example, (Policy1, SomeTokens) or (Policy2, SomeOtherTokens).

Also, a transaction might simultaneously mint some tokens and burn others.

The native token lifecycle¶

The native token lifecycle consists of five main phases:

minting

issuing

using

redeeming

burning

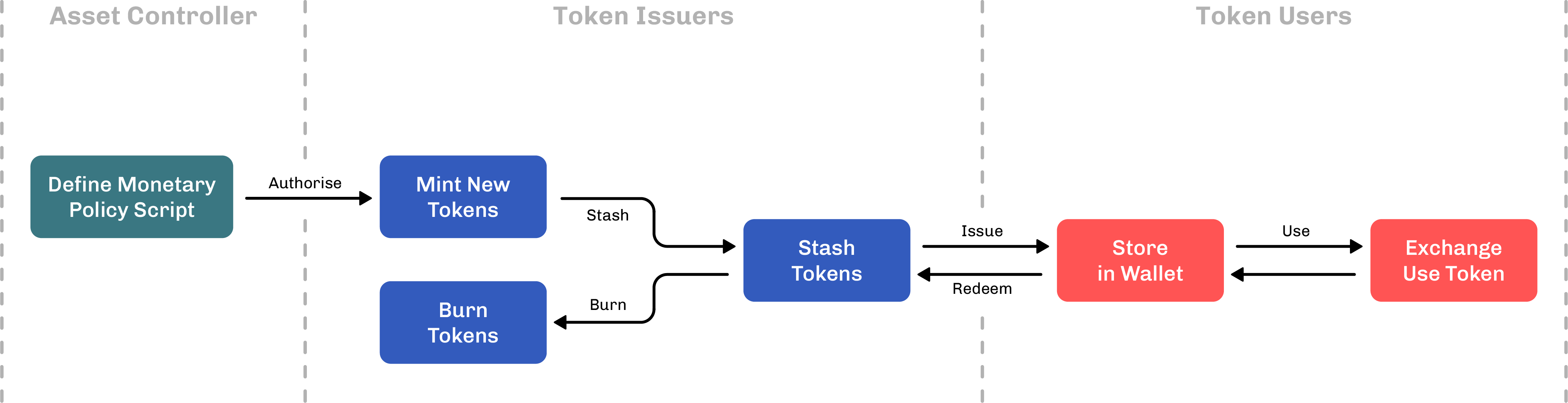

The following diagram outlines the interaction between the system components:

Each of these logical phases involves transactions on the Cardano blockchain, which may incur fees in ada. The main groups of actors are:

Asset controllers, who define the policy for the asset class, and authorise token issuers to mint/burn tokens. They may also retain co-signing rights for any tokens that are issued/burnt.

Token issuers, who mint new tokens, maintain the reserve of tokens in circulation, issue them to token holders, and burn tokens when they are no longer of use.

Token holders, who hold tokens, send them to other users, use them for payment, and who may redeem them with the issuers when they have finished using them. Token users may include normal users, exchanges etc.

The lifecycle of multi-asset tokens starts with their creation – minting, which refers to the process whereby new tokens are created by one or more token issuers in accordance with the monetary policy script that the asset controller has defined. New tokens will usually be created to fulfil specific purposes. For example, fungible or non-fungible (unique) tokens may be created to be used for specific payment, purchasing, or exchange needs. When a new token is minted, the total token supply for that token increases, but there is no impact on the ada supply. Minting coins and transferring them to new addresses may require an ada deposit to be paid, which may be proportional to the number of different tokens that are held, for example.

Token holders will hold tokens in their wallets, may pass them on to other users, exchange them for items of value (including non-native tokens), etc. in exactly the same way that they can use ada. When a user has finished using the token, they may choose to redeem them. This means that tokens are returned to an issuer (perhaps in return for a product, service, or some other currency, for instance). Once redeemed, tokens could then be re-issued to other users as needed. Token holders will need to maintain some ada in their wallets to pay for transaction fees.

When tokens become redundant, they can be burned, if desired, in accordance with the underlying monetary policy script. The process of burning destroys these tokens (removes them from circulation), and the total token supply decreases. Any deposits will be returned at this point. The burning process is identical for fungible and non-fungible tokens.

Note: The multi-asset token lifecycle potentially allows tokens to be obtained and reissued by other parties - token holders who act as reissuers for the token. This can be done to e.g., enable trading in multiple asset classes, maintain liquidity in one or more tokens (by acting as a broker), or to eliminate the effort/cost of token minting, issuing or metadata server maintenance. Thus, both reissuers and issuers can gain from such a deal - eliminating cost and effort, maintaining separation and integrity, and injecting value into the asset class.